Why Were Chinese Workers Continually Harassed and Attacked Brainly

Our world is confronting the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. As of May 2020, the World Health Organization (2020) declared there are more than three million confirmed cases of Covid-19 in 213 countries, areas and territories. The outbreak of Covid-19 has sent billions of people into lockdown, health services into crises, and economies into turmoil worldwide.

While anxiety and fear about the pandemic have been widespread, racist incidents, including hate crimes and Asian-focused racism, have also occurred, particularly in the United States. The Asian population, the fastest growing ethnic group in the U.S. (Lopez et al., 2017), has become targets of discrimination, harrassment, racial slurs, and physical attacks. Negative attitudes and prejudice toward Asian Americans are trending upwards as more and more Covid-19 cases and deaths are confirmed in the U.S. The FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) also said that as Covid-19 grows, hate crimes against Asian Americans will more than likely increase as well (Margolin, 2020). This study explores these negative attitudes toward Asian-Americans. Specifically, this study explores how prejudice toward Asian-Americans during the Covid-19 pandemic is related to social media use.

As of early 2020, many parts of the world have been in physical isolation due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Due to physical and social isolation, people increasingly rely on social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, etc. to facilitate human interactions and keep themselves up to date with information. Also, authorities use situational information to organize official Covid-19 related posts on their social media platforms to popularize their response strategies to the public (Li et al., 2020). For example, United Nation (2020) statistics from April 8, 2020 state, there are 167 countries using national portals and social media platforms to engage people and provide vital information against Covid-19. Consequently, social media plays a crucial role in the public's perceptions and significantly influences their communication during a crisis (Schultz et al., 2011).

In recent years, social media platforms have been used as a tool to express people's reactions, thoughts and opinions on current events (Chavez-Dueñas and Adames, 2018). However, according to recent research, social media also creates a playground for racism; and people of different races have experienced discrimination online because of their race (appearance or accent related) (Yang and Counts, 2018). Moreover, Relia et al. (2019) have said the proportion of discrimination on social media is strongly related to the number of hate crimes across 100 cities in the U.S. For instance, Trump's presidential campaign concentrated on Twitter usage and his tweets about Islam-related topics have been correlated with hate crimes toward Muslims (Müller and Schwarz, 2019). The findings of Müller and Schwarz's study (2019) stated social media accounts for the spread of anti-Muslim hate crimes since the start of Trump's 2016 presidential campaign.

People also use social media to oppose unfair treatment based on race or to support anti-racism activism (Chavez-Dueñas and Adames, 2018). Similarly, following the election of Barack Obama, the first African American president in the U.S., in 2008, words like "post-racial" and "colorblind" became popular in many social media outlets (Bonilla-Silva, 2010). These popular words have suggested the historic election minimized the role of race in the lives of many ethnic groups in the U.S. (López, 2009). In recent years, more and more people have used Twitter as a platform to promote social and racial activism by creating hashtags such as #BlackLivesMatter or #SayHerName (Chavez-Dueñas and Adames, 2018).

In the U.S., social media has become a means to either discriminate against Asian Americans or to fight against prejudice. Media outlets have been considered as one of the main factors contributing to discrimination and xenophobia (Aten, 2020). Some media outlets have had misleading headlines such as "Chinese virus pandemonium" or "China kids stay home" (Wen et al., 2020). As of early April 2020, there have been around 72,000 posts with hashtag #WuhanVirus and 10,000 others with hashtag #KungFlu on Instagram (Mcguire, 2020). In the U.S., across social media, posts like these have negatively impacted the Asian community and are unlikely to stop (Aten, 2020). Such posts have flamed anti-Asian sentiment, with acts of anti-Asian violence in direct response to fears of Covid-19 being reported. For example, a man in Texas attempted to kill an Asian-American family including a 2-year-old and a 2-year-old in late March 2020 (Melendez, 2020). Such an attack represents a potential surge of hate crimes toward Asian Americans amid the Covid-19 outbreak in the U.S. (Margolin, 2020).

In contrast, social media platforms also deliver messages to help counter prejudice/discrimination against the Asian community. Social media firms like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook have all taken action. Their platforms have been used to support those suffering from abuse. Campaigns such as posts including hashtag #IAmNotAVirus have been promoted atop user feeds on their sites (Mcguire, 2020). In general, depending on different types of messages and distribution platforms, public's perceptions on social media vary, particularly in such crisis like Covid-19 pandemic.

Prejudice and fear toward Asians have increased in the U.S. during the Covid-19 pandemic. Drawing on prejudice and intergroup contact research (Allport, 1954; Stephan and Stephan, 2000; Croucher, 2013) First, such negative sentiments, particularly via social media demonstrate how the dominant cultural group (predominantly Caucasian) express their fears and hatred toward Asians (a minority group) and a fear of coming into contact with the virus. One explanatory reason for anti-Asian attitudes is threat perception. Stephan and Stephan (1996) in their integrated threat theory (ITT) proposed four types of threat: realistic threats, symbolic threats, stereotypes, and intergroup anxiety, may cause prejudice. Since then, these types of threat have been a framework for understanding, explaining, and predicting prejudice and negative attitudes toward minorities (Croucher, 2013).

Integrated Threat Theory

Prejudice and discrimination do not have a single cause; instead, they are the result of negative attitudes or beliefs of the in-group toward out-group members (Allport, 1954). One of the explanatory factors of these negative emotions or hostility is threat perception. Stephan and Stephan (1993, 1996) stated that when the in-group members believe their values or beliefs are threatened by the out-group, negative attitudes emerge as defensive mechanisms.

In line with Allport's research on prejudice, Stephan and Stephan (1993, 1996, 2000) developed integrated threat theory (ITT). The theory includes four kinds of threat that explain and predict negative attitudes toward minority groups: realistic threats, symbolic threats, intergroup anxiety, and negative stereotypes (Croucher, 2013). According to ITT, intergroup feelings of threat and fear result in prejudice and discrimination (Stephan and Stephan, 2000). The key to ITT is that threat does not need to be real, the perception of threat is enough to lead the ingroup (a dominant cultural group) to have and express negative attitudes, prejudice, and hate toward an out-group (a minority group).

Realistic threats are related to concerns posed by the out-group to the in-group's existence (Stephan and Stephan, 1996). Realistic threats emphasize threats to welfare, political and economic power, physical and material well-being of the in-group and its members. Moreover, Stephan and Stephan (2000) stated realistic threats lead to prejudice whether the threat is real or not.

Symbolic threats describe concerns to the ingroup's "way of life," which is different from "morals, values, standards, beliefs and attitudes of the out-group (Stephan and Stephan, 1996). These threats occur when members of the ingroup feel their "way of life" perceptions are threatened by the outgroup. Perceived symbolic threats predict prejudice as perceptions of cultural differences indirectly affect attitudes toward the out-group (Spencer-Rodgers and McGovern, 2002).

Stephan and Stephan (2000) have argued intergroup anxiety occurs when people feel personally threatened while having intergroup interactions since they are worried about individually negative outcomes. On the other hand, negative outcomes result from the fear of embarrassment, rejection, or ridicule (Stephan and Stephan, 2000). Islam and Hewstone (1993) argued when the out-group has more advantages (perceived or real) than the in-group, intergroup anxiety arises; and this is a result of dislike toward the out-group members. Stephan and Stephan (1996) have also argued intergroup anxiety directly causes negative expressions toward out-group members.

Negative stereotypes are the in-group's assumptions about the out-group. These assumptions are implied threats to the in-group because while having an interaction, the in-group members are often afraid of negative effects (Croucher, 2017). For example, if in-group members assume members of the out-group are dishonest or aggressive, they will expect negative interactions with them. Consequently, in-group members might dislike out-group members (Stephan W. G. et al., 2000). The stereotypes of the outgroup may consist of threats to the in-group when the out-group does not meet the ingroup's social or behavioral expectations (Hamilton et al., 1990). Studies have shown that negative stereotypes exist in social media (Levy et al., 2013), as stereotypes about social groups are one form of media content (Bissell and Parrott, 2013). Consequently, social media often reinforce prejudice (Davidson and Farquhar, 2020).

The digital era is characterized by an unprecedented number of media and the invention of new platforms available to both professional journalists and the public. Also, raising digital intergroup/intercultural contacts are increasingly affecting the quantity and quality of intergroup dynamics such as prejudicial messages disseminated via social media. The level of prejudice in social media is linked to the selective exposure to media and type of media content, and the resulting polarization, described as the deepened tendency toward the chosen source of media exposure (Davidson and Farquhar, 2020). However, as different social platforms provide various content production and distribution facilities, the quality of produced messages could vary across these media, which could be explained by the notion of media richness.

Media Richness Theory (MRT) posits that richness of medium and equivocality of task influence the media chosen for communication (Ishii et al., 2019). MRT bases media richness on the availability of immediate feedback, multiple cues, language variety, and personal focus. Later on, social information and individual experiences were also added to the measures of media richness (Ishii et al., 2019). Recent studies have expanded MRT to social media and showed there is a valance variation in the ability of social media to convey specific types of messages; for example, the perceived media richness of Instagram was found to be more related to young adults' self-presentation via photos and videos while on Facebook and Twitter it more relies on openness in writing (longer or shorter) texts (Lee and Borah, 2020).

Social media is a platform often used to communicate prejudice (Davidson and Farquhar, 2020). During the Covid-19 pandemic in the U.S., prejudice, hatred, and other forms of negative sentiments have been expressed on social media toward Asian Americans, particularly Chinese Americans (Mcguire, 2020). Moreover, the extent to which these media vary in levels of media richness differs. Thus, to understand the extent to which during the Covid-19 pandemic in the U.S. that social media use is related to prejudice toward Asian Americans, in particular Chinese Americans the following research question is proposed:

RQ: During the Covid-19 pandemic in the United States, to what extent does social media use predict prejudice toward Chinese Americans?

Method

To answer the research question, we collected data in the U.S. via an online survey with the assistance of Qualtrics, a research firm. Online participant panels, such as Qualtrics have been shown to be comparable in composition to other population in prior research (Roulin, 2015; Troia and Graham, 2017). Qualtrics provided a small amount of compensation to each respondent. We included various quality checks (analysis of Means, and Standard Deviations) that led to a final sample of 288. We received ethical approval before data collection began. The survey included a series of demographic questions, a measure of social media use, and scales assessing integrated threat.

Participants

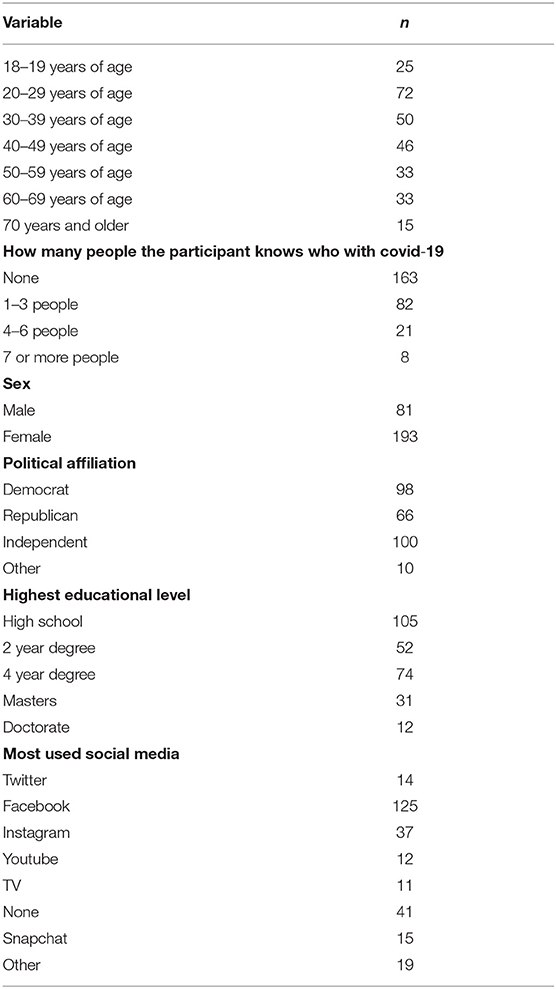

Participants for this study included 288 participants. Participants not born in the U.S. were removed from the sample for final analysis, leaving a final sample of 274 participants. Participants not born in the U.S. were removed so that the sample only included native born individuals to remove nation of birth as an additional point of comparison. All participants were Caucasian (White). Table 1 presents the full demographic information.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Measures

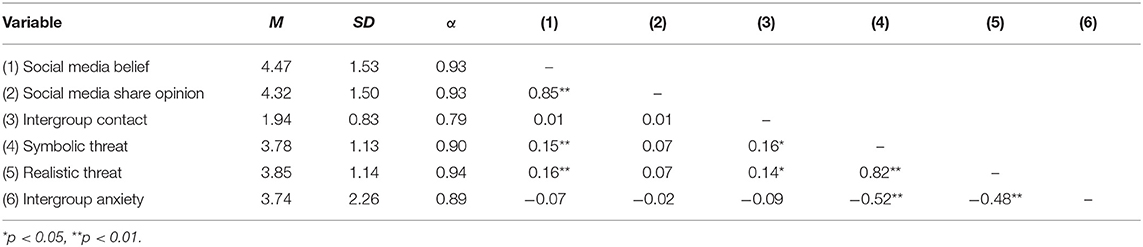

All surveys included demographic questions and the following measures: Social Media use (Believe and Share Opinion) (Spencer and Croucher, 2008), Measure of Intergroup Contact (Gonzalez et al., 2008), Measure of Symbolic Threat (Stephan et al., 1999), Measure of Realistic Threat (Stephan et al., 1999), and the Intergroup Anxiety Scale (Stephan and Stephan, 1985). See Table 2 for the means, standard deviations, correlations, and alphas associated with the study variables. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to ensure the validity and reliability of the study constructs. CFA using social media belief and social media share opinion showed acceptable fit: χ2(17) = 37.71, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.02, RMSEA = 0.07, PClose = 0.17 (Hu and Bentler, 1999). CFA using contact, symbolic threat, realistic threat and intergroup anxiety also showed excellent fit: χ2(112) = 231.57, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.06, RMSEA = 0.06, PClose = 0.05.

Table 2. Means, standard deviation, reliability coefficients, and correlations.

Social Media Use

Social media use was measured using eight Likert-type questions from Spencer and Croucher (2008). The eight items make up two factors: Believe the Media and Share its Opinion. The items measure a participant's perception of their most used daily social media in terms of: how much they believe it, think it is fair, think it is accurate, think it presents the facts, think it is concerned about the public, represents their own opinion, and represents their own opinion on Covid-19. In addition, one question asks participants to identify the social media they use on a daily basis and a final question asks the participants to identify their most used daily social media. Reliabilities have ranged from 0.70 to 0.80 (Spencer and Croucher, 2008; Spencer et al., 2012).

Integrated Threat

Integrated threat was assessed using a Measure of Intergroup Contact (Gonzalez et al., 2008), Measure of Symbolic Threat (Stephan et al., 1999), Measure of Realistic Threat (Stephan et al., 1999), and the Intergroup Anxiety Scale (Stephan and Stephan, 1985).

Measure of Intergroup Contact

Four items from Gonzalez et al. (2008) measured intergroup contact. The items were: "How many Chinese friends do you have?" This item was rated from (1) none to (4) only Chinese friends. The remaining three items were: "Do you have contact with Chinese students or co-workers?" "Do you have contact with Chinese in your neighborhood?" and "Do you have contact with Chinese somewhere else, such as at a sports club or other organization?" These items were rated from (1) never to (4) often. The alpha for the scale was 0.70 in the Gonzalez et al. (2008) study and has ranged from 0.75 to 0.90 in other research (Croucher, 2013; Croucher et al., 2013).

Measure of Symbolic Threat

Three items measured symbolic threat (Stephan et al., 1999). The items were: "American identity is threatened because there are too many Chinese today," "American norms and values are threatened because of the presence of Chinese today," and "Chinese are a threat to American culture." "Chinese" was used as the target group for prejudice due to the high amount of social media commentary directed toward "China," "the Chinese" and "Chinese Americans" in relation to Covid-19, as opposed to other Asian groups. Responses ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. A higher score indicated a stronger feeling of threat. The scale has shown high reliability in previous research, 0.89 (Gonzalez et al., 2008) and 0.85 to 0.90 (Croucher, 2013; Croucher et al., 2013).

Measure of Realistic Threat

The measure of realistic threat included three statements that assessed the effects of Chinese on the economic situation in the U.S. The statements included: "Because of the presence of Chinese, Americans have more difficulties finding a job," "Because of the presence of Chinese, Americans have more difficulties finding a house," and "Because of the presence of Chinese, unemployment will increase." Responses ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Higher scores indicate more threat. This scale has also shown reliability, 0.80 (Gonzalez et al., 2008) and 0.82 to 0.86 (Croucher, 2013).

Intergroup Anxiety Scale

Stephan and Stephan's (1985) 10-item semantic differential Intergroup Anxiety Scale assessed the extent to which respondents have an affective/emotional response to interacting with outgroup members in an ambiguous situation. The items are rated on a 10-point scale from 1 not at all to 10 extremely. Reliabilities have ranged from 0.86 (Stephan and Stephan, 1985) to 0.91 (Hopkins and Shook, 2017).

Analysis and Results

To answer the research question, three multiple regressions were constructed using symbolic threat, realistic threat, and intergroup anxiety as the criterion variables. The following predictor variables were included in each multiple regression: intergroup contact, social media belief, social media share opinion, sex, political affiliation, educational level, number of people the participant knows with Covid-19, and most used daily social media outlet. Research has shown sex, political affiliation, and education differ in attitudes toward out-group members. For example, research has shown women have more implicit racial prejudice toward minorities than men because women are more concerned about crime threats from out-group members (Valentova and Alieva, 2013). Political affiliation also predicts attitudes toward immigrants (Hawley, 2011). Meeusen et al. (2017) said prejudice against immigrants differ in political parties; thus, it also affects voters in diverse ways. Furthermore, education has a strong effect on prejudice (Carvacho et al., 2013). Hello et al. (2002) stated varied levels of education have different influences on prejudice, with more educated individuals showing lower levels of prejudice. Dummy variables were therefore created for political affiliation, and most used daily social media outlet. Cross-produce terms were generated to test for interaction effects. Interaction effects were tested using a hierarchical regression analysis (Pedhazur, 1997).

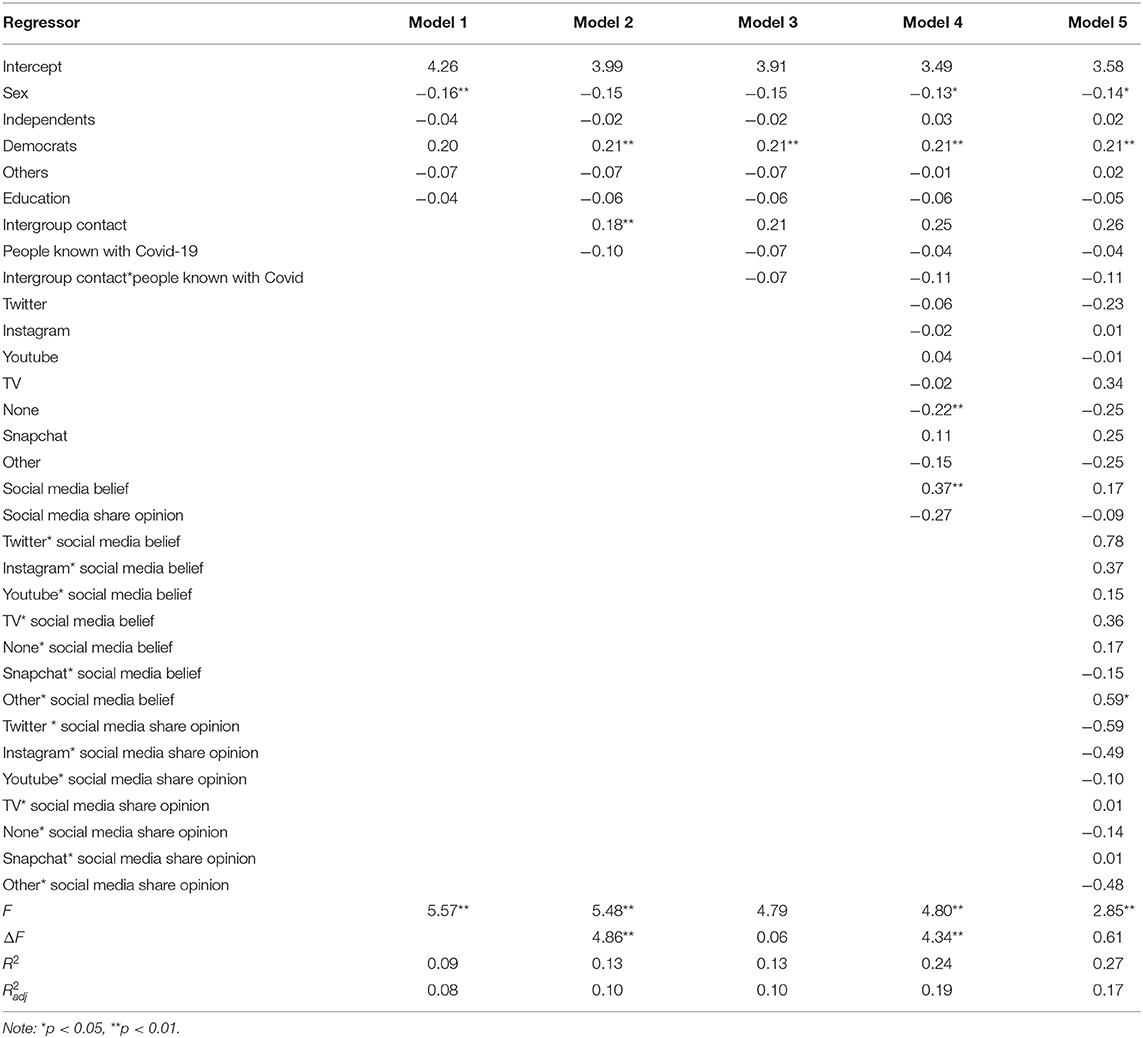

Multiple hierarchical regression modeling was used to test the research question. For each multiple regression, five models were created. The regression results are presented in Tables 3–5. For symbolic threat (Table 3), in model 1, sex, education, and political affiliation were entered as predictors (R 2 = 0.09). In model 2, intergroup contact and the number of individuals known with Covid-19 were entered as predictors (R 2 = 0.13). The nested F statistic comparing model 1 and model 2 was significant (ΔF = 4.86, p < 0.01). In model 3, a cross-product for intergroup contact and individuals known with Covid-19 was entered (R 2 = 0.13). This model was not a significant improvement over model 2 (ΔF =0.06, p = ns). In model 4, most used daily social media, social media belief, and social media share opinion were entered (R 2 = 0.24). This model was a significant improvement over model 3 (ΔF = 4.34, p < 0.01). In model 5, cross-product terms for most used daily social media and social media belief, and most used social media and social media share opinion were entered (R 2 = 0.27). This model was not a significant improvement over model 4 (ΔF = 0.61, p = ns). As model 4 had the most significant explanatory power of the models, it was retained for the final analysis. As Table 3 reveals, various independent variables predict symbolic threat. Sex was a significant predictor of symbolic threat (b = −0.13, p < 0.05), with males scoring lower on symbolic threat than female respondents. Democrats (b = 0.21, p < 0.01) scored higher on symbolic threat than Republicans. Individuals who reported not using social media on a daily basis scored significantly lower on symbolic threat (b = −0.22, p < 0.01) than those who identify Facebook as their most used daily social media. Finally, there is a significant positive relationship between symbolic threat and the extent to which an individual believes their most used daily social media score (b = 0.37, p < 0.01).

Table 3. Regression model for symbolic threat.

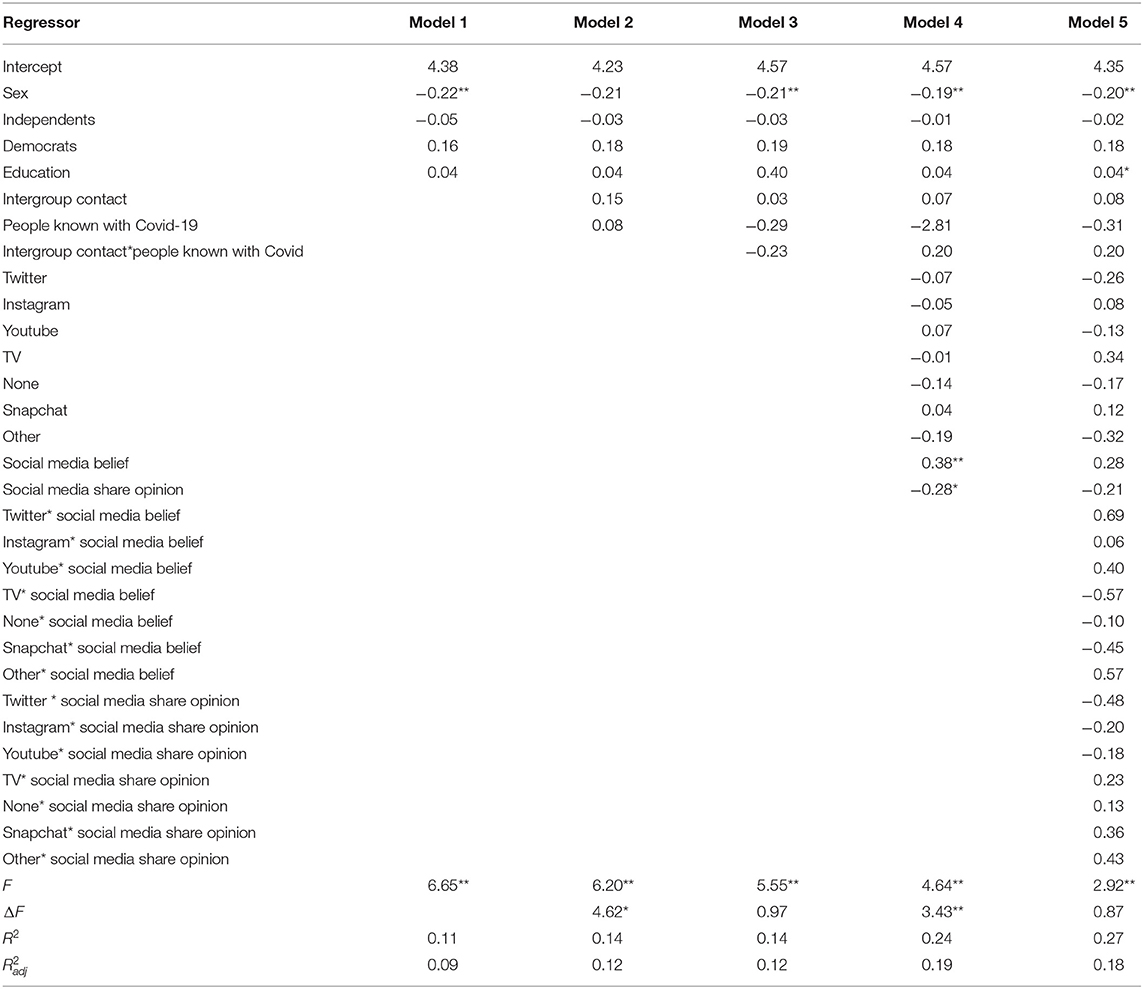

For realistic threat (Table 4), in model 1, sex, education, and political affiliation were entered as predictors (R 2 = 0.11). In model 2, intergroup contact and the number of individuals known with Covid-19 were entered as predictors (R 2 = 0.14). The nested F statistic comparing model 1 and model 2 was significant (ΔF = 4.62, p < 0.01). In model 3, a cross-product for intergroup contact and individuals known with Covid-19 was entered (R 2 = 0.14). This model was not a significant improvement over model 2 (ΔF = 0.97, p = ns). In model 4, most used daily social media, social media belief, and social media share opinion were entered (R 2 = 0.24). This model was a significant improvement over model 3 (ΔF = 3.43, p < 0.01). In model 5, cross-product terms for most used daily social media and social media belief, and most used social media and social media share opinion were entered (R 2 = 0.27). This model was not a significant improvement over model 4 (ΔF = 0.87, p = ns). As model 4 had the most significant explanatory power of the models, it was retained for the final analysis. As Table 4 reveals, various independent variables predict realistic threat. Sex was a significant predictor of realistic threat (b = −0.19, p < 0.01), with males scoring lower on realistic threat than female respondents. There is a significant positive relationship between realistic threat and the extent to which an individual believes their most used daily social media score (b = 0.38, p < 0.01), and a negative relationship between realistic threat and sharing opinions with social media (b = −0.28, p < 0.01).

Table 4. Regression model for realistic threat.

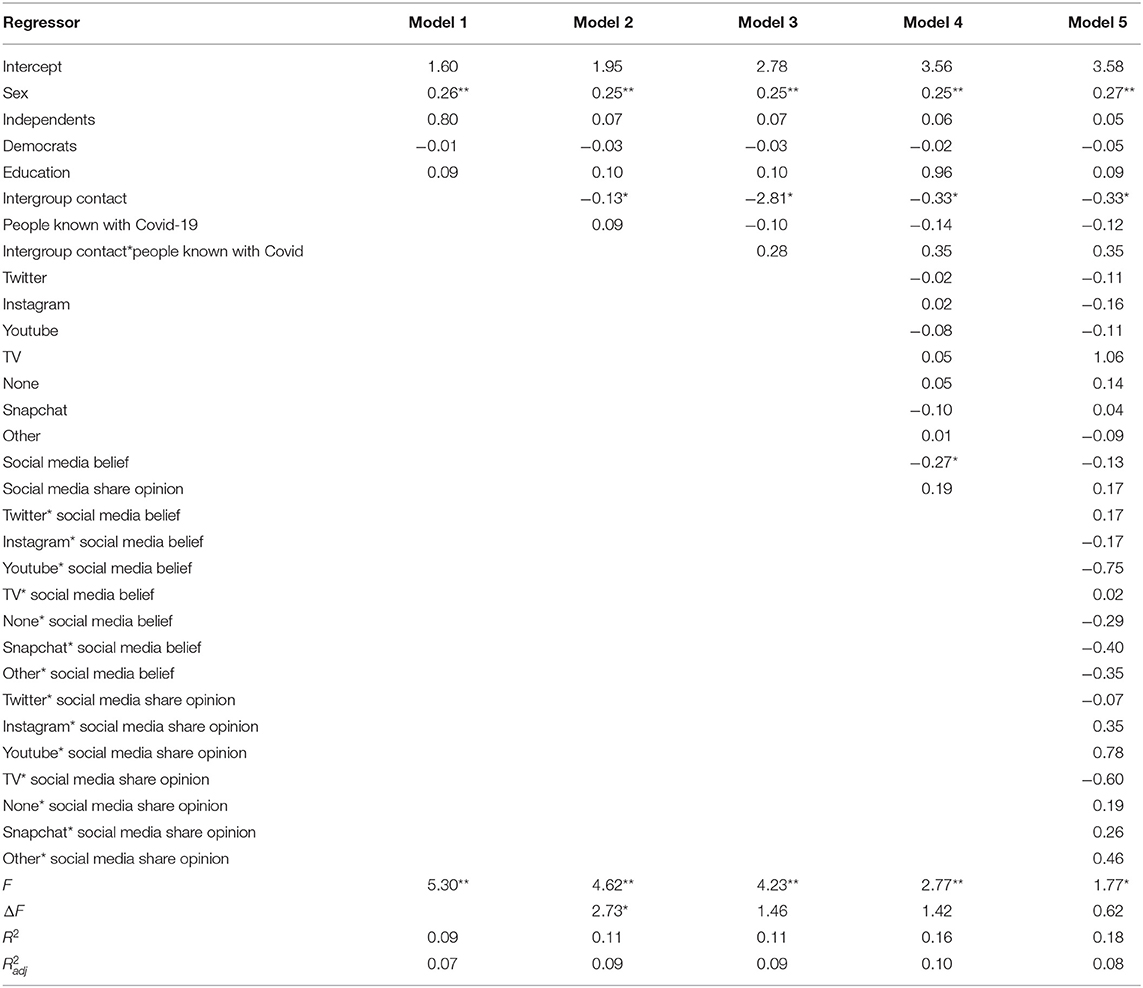

For intergroup anxiety (Table 5), in model 1, sex, education, and political affiliation were entered as predictors (R 2 = 0.09). In model 2, intergroup contact and the number of individuals known with Covid-19 were entered as predictors (R 2 = 0.11). The nested F statistic comparing model 1 and model 2 was significant (ΔF = 2.73, p < 0.05). In model 3, a cross-product for intergroup contact and individuals known with Covid-19 was entered (R 2 = 0.11). This model was not a significant improvement over model 2 (ΔF = 1.46, p = ns). In model 4, most used daily social media, social media belief, and social media share opinion were entered (R 2 = 0.16). This model was a significant improvement over model 3 (ΔF = 1.42, p = ns). In model 5, cross-product terms for most used daily social media and social media belief, and most used social media and social media share opinion were entered (R 2 = 0.18). This model was not a significant improvement over model 4 (ΔF = 0.62, p = ns). As model 2 had the most significant explanatory power of the models, it was retained for the final analysis. As Table 5 reveals, sex and intergroup contact predicted intergroup anxiety. Sex was a significant predictor of intergroup anxiety (b = 0.25, p < 0.01), with males scoring higher on intergroup anxiety than female respondents. Finally, there is a significant negative relationship between intergroup anxiety and intergroup contact (b = −0.13, p < 0.05).

Table 5. Regression model for intergroup anxiety.

In sum, social media's predictive influence on prejudice is mixed. Social media had no statistical effects on intergroup anxiety. Intergroup contact had a negative effect on intergroup anxiety. However, the more a social media user believes their most used daily social media is fair, accurate, presents the facts, and is concerned about the public (social media belief), the more likely that user is to believe Chinese Americans pose a realistic and symbolic threat. In addition, respondents who do not use social media on a daily basis are less likely than those who use Facebook to perceive Chinese Americans as a symbolic threat. Interestingly, there is a negative relationship between the extent to which a respondent shares their opinions with social media outlets and realistic threat. Essentially, there is an inverse relationship between sharing opinions with social media and realistic threat: more similar opinion lower threat, less similar opinion higher threat. Democrats scored higher on symbolic threat than Republicans on symbolic threat, while political affiliation had no effect on other types of prejudice. Men and women significantly differed on each type of prejudice, with men scoring higher on intergroup anxiety and women higher on symbolic and realistic threat.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the extent to which social media use predicts prejudice toward Chinese Americans during the Covid-19 pandemic in the United States. Three general conclusions emerged from the data. First, results revealed sex plays a significant role in predicting realistic threats and intergroup anxiety among Americans toward out-group members (in this case, Chinese Americans). Women feel more threatened than men as they are more likely to believe the presence of Chinese Americans has a negative influence on their welfare, political and economic power, physical and material well-being such as difficulties finding a job or a house and increases unemployment. Even if the threat is not real, in-group members have prejudicial attitudes to out-group members (Stephan and Stephan, 2000). Maddux et al. (2008) asserted realistic threats account for prejudice and negative emotions toward ethnic groups. Men have more intergroup anxiety than women, as they personally perceive more threats when having intergroup interactions. This is a clear indicator that men feel more awkward, irritated, suspicious, anxious, defensive, and self-conscious while having communicative interactions with Chinese Americans. Such feelings directly cause negative expressions toward out-group members (Stephan and Stephan, 1996). Also, intergroup anxiety is a powerful and consistent predictor of prejudice against ethnic groups (Stephan et al., 1998). Together, these results show women tend toward more cognitive fears of Chinese Americans (realistic and symbolic) while men tend to have more affective fears (intergroup anxiety) of Chinese Americans, at least during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Second, social media belief or sharing of opinions was not related to intergroup anxiety. There is debate over the conceptualization of intergroup anxiety as a predictor of negative attitudes. Riek et al. (2006), in their meta-analysis showed how researchers increasingly replace intergroup anxiety with group self-esteem. Moreover, more and more ITT researchers have reduced the original four ITT threats (realistic threat, symbolic threat, intergroup anxiety and negative stereotypes) to only realistic and symbolic threats (Stephan and Renfro, 2002; Stephan et al., 2009; Nshom and Croucher, 2017, 2018). Thus, while the construct of intergroup anxiety still relates to the other ITT constructs (realistic and symbolic threat and intergroup contact) in this study, it is possible that intergroup anxiety is not the most applicable construct to link with social media use. As social media has been extensively linked to the promotion of self-esteem (Blachnio et al., 2016; Hawi and Samaha, 2017), a more practical way to measure the relationship between social media and "anxiety" could be to explore group self-esteem as a substitute for intergroup anxiety. Exploring how social media use influences one's self-esteem during a pandemic might provide a more nuanced and fruitful understanding of how threats to self-esteem are impacted by perceived threats from potential virus carriers or those blamed for carrying the virus in the media.

Third, the distinction between intergroup anxiety and other threat factors in ITT is also evident in the relationship between belief in social media, and media representation of one's opinion and ITT. The study showed that higher levels of believing one's preferred social media predicts increased symbolic and realistic threat and decreased intergroup anxiety. The impact of belief in social media on symbolic and realistic threats could reflect social media content during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which resentment about the outcome of COVID-19 is associated with higher levels of prejudice toward the outgroup perceived to be responsible for the virus. This is in line with social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979), which indicates that group identification is based on maximizing the positive aspects of ingroup and negative aspects of the outgroup. The maximization of the negative aspects of the outgroup during the Covid-19 pandemic, Chinese Americans, has caused an increase in how the symbolic (i.e., the new lifestyle and social relationships and distancing), and unpleasant realistic aspects of the virus (i.e., economic hardship, unemployment and stockpiling) are ascribed and perceived. Sharing opinions with a preferred social media, however, had a negative impact on realistic threat and no impact on symbolic threat and intergroup anxiety. Based on spiral-of-silence (Noelle-Neumann, 1993), a lower level of being exposed to one's opinion in the media increases the perception that one is in the minority position, which can decrease one's self-esteem in dealing with intergroup situations, especially realistic situations that have more immediate economic effects. Both media belief and sharing opinions showed a distinctive effect on intergroup anxiety, which could be related to the varied nature of intergroup anxiety, which functions at the individual level compared to the other ITT factors which define threat at the group level (Rahmani, 2017). While believing and relating to media message were related to the one of some forms of integrated threat, the study found no difference among the various type of media in perceiving intergroup threat. This could be related to the similar content of the social media, as the main media for most of the participant, which provide a platform for the various mass media to disseminate their content.

Fourth, the study showed men have more intergroup anxiety while their realistic and symbolic threat levels are lower. This finding could be related to higher position of males in the more patriarchal American society where males perceive to lose more should the status quo change. Rye et al. (2019) used the same stance to explain the why threat to gender norms could be more distressing for males and Stephan C. W. et al. (2000) mentioned that as most American women have accepted inevitability of male economic and political hegemony, they do not perceive males to be a realistic threat. Higher levels of intergroup anxiety can be related to the individual nature of this threat compared realistic and symbolic threat. This is in line with previous studies that showed perception of threat about transgender individuals, males showed more hostile sexism while for female the same process included more internalized and personal hatred or hostility (Rye et al., 2019).

Fifth, the results showed that those respondents who identified as Democrats reported higher levels of symbolic threat from Chinese Americans. Essentially, this result shows that Democrats, as opposed to Republicans see Chinese Americans as posing a higher risk to the U.S. cultural way of life. This result is counter to previous work on political affiliation and prejudice (Hawley, 2011; Meeusen et al., 2017). This result is also counter to the work of Gries and Crowson (2010) who explored American prejudice toward China and found Democrats have lower prejudice than Conservatives. While the results of the current study are statistically significant, further research should be conducted to validate this finding in different samples to ascertain whether during a crisis (such as a pandemic) political merging or shifts of values/ideas could take place toward an outgroup.

Future Research and Recommendations

Research has demonstrated that stereotypes are perpetuated on social media and that social media often reinforce prejudice (Bissell and Parrott, 2013; Levy et al., 2013; Davidson and Farquhar, 2020). The findings from this study provide further evidence that social media use reinforces the elements of intergroup threat which could lead to prejudice. Specifically, during the Covid-19 pandemic in the U.S., the more an individual believes their most used daily social media is fair, accurate, presents the facts, and is concerned about the public (social media belief), the more that person sees Chinese Americans as a realistic and symbolic threat. Further research can reveal the extend of media use impact on prejudice. Also, to better understand this relationship, it is important for future research to look at how Chinese Americans and other groups have been framed/portrayed on social media. In depth analyses of these messages could facilitate a critical awareness of how social media messages have introduced or reinforced blame for realistic and symbolic threats from Chinese Americans for Covid-19.

As the world continues to grapple with Covid-19, instances of prejudice and blaming minorities for the spread of the virus outside of the U.S. should be examined and compared. As of May 6, 2020, there were a total of 3,656,644 global confirmed Covid-19 cases, with 1,202,246 of those in the U.S. (Johns Hopkins University Covid-19 Dashboard, 2020); the reaming cases were from around the globe. While the current study explores how prejudice toward Chinese Americans during the Covid-19 pandemic is related to social media use in the U.S., prejudice toward other groups in other nations has grown dramatically (Muzi, 2020; Serhan and McLaughlin, 2020; Sim et al., 2020). As the virus spreads around the world, so has prejudice, xenophobia, and racism. To better defend against and rebuild from the virus it is essential we understand how societies are socially responding to the virus. To what extent are societies and cultural groups blaming each other for its spread? To what extent is social media being used to unite or divide against Covid-19? What is the social cost of Covid-19? Such questions are crucial to our Covid-19 response and must be discussed.

Knowing what we know about social media's influence on prejudice during the Covid-19 pandemic, we propose governments and health care industries use social media to combat Covid-19 prejudice. While many governments (like New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Finland, etc.) have developed well-organized campaigns (television, radio, and social media) to educate their populations on the risks of Covid-19, prevention, governmental steps and actions, such campaigns should do more to explicitly combat Covid-19 prejudice and racism. Such campaigns should respond to prejudicial and racist incidents by directly discussing the social cost of Covid-19 prejudice and racism. Moreover, while many nations remain in different levels of lockdown and adjust to social distancing, health practitioners could use social media to explore new techniques to communicate ways to reduce transmission of Covid-19. Governments have already been using social media to encourage social distancing and to promote better health practices, through social media health practitioners can continue these practices.

This study has two limitations. First, as this study is a cross-sectional study it does not show causality. The study cannot demonstrate that social media causes prejudice, only that there is a correlation between social media use and prejudice. Future research should be conducted using longitudinal and/or experimental designs to examine potential causal relationships between social media use and prejudice. Second, the integrated threat items used the term "Chinese" to identify the target group for participants. It is possible that this term might have confused participants in that participants may have answered questions in terms of "Chinese Americans," "the Chinese," "China" or "Chinese culture," etc. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, knowing that the term, "Chinese" in the measure could have caused some confusion.

This study is one of the first attempts to examine the extent to which social media use predicts prejudice toward a minority group (Chinese Americans) blamed for the spread of a virus (Covid-19). The results reveal social media use has a significant influence on prejudice toward Chinese Americans. The more a social media user believes their most used daily social media, the more they believe Chinese Americans are a realistic and symbolic threat to the U.S. With cases of Covid-19 continuing to increase globally, so does prejudice, racism, and violence against those individuals and/or groups who are blamed for carrying and spreading the virus. Vince (2020) argued that our tribal culture influences how we see the world more than facts. She added that Americans tend to adopt the opinions of their tribal elites, often political leaders and celebrities. These opinions once shared via social media are deemed fact. As Covid-19 grips the U.S., the nation with the highest numbers of cases in the world as of May 2020, it's critical we understand not only the human but also the social costs of the virus to have any chance at slowing and stopping its spread.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Massey University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Allport, G. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Google Scholar

Bissell, K., and Parrott, S. (2013). Prejudice: the role of the media in the development of social bias. J. Commun. Monogr. 15, 219–270. doi: 10.1177/1522637913504401

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., and Rudnicka, P. (2016). Narcissism and self-esteem as predictors of dimensions of Facebook use. Pers. Individ. Dif. 90, 296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.018

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2010). Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and Racial Inequality in Contemporary America. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Google Scholar

Carvacho, H., Zick, A., Haye, A., González, R., Manzi, J., Kocik, C., et al. (2013). On the relation between social class and prejudice: the roles of education, income, and ideological attitudes. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 43, 272–285. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1961

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., and Adames, H. Y. (2018). #Neotericracism: exploring race-based content in social media during racially charged current events. Rev. Interam. Psicol. Interam. J. Psychol. 52, 3–14. doi: 10.30849/rip/ijp.v52i1.493

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Croucher, S. M. (2013). Integrated threat theory and acceptance of immigrant assimilation: an analysis of muslim immigration in Western Europe. Commun. Monogr. 80, 46–62. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2012.739704

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Davidson, T., and Farquhar, L. (2020). "Prejudice and social media: attitudes toward illegal immigrants, refugees, and transgender people," in Gender, Sexuality and Race in the Digital Age, eds D. N. Farris, D. R. Compton, and A. P. Herrera (New York, NY: Springer), 151–167.

Google Scholar

Gonzalez, K. V., Verkuyten, M., Weesie, J., and Poppe, E. (2008). Prejudice towards Muslims in the Netherlands: testing integrated threat theory. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 667–685. doi: 10.1348/014466608X284443

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gries, P. H., and Crowson, H. M. (2010). Political orientation, party affiliation, and American attitudes towards China. J. Chin. Political Sci. 15, 219–244. doi: 10.1007/s11366-010-9115-1

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hamilton, D. L., Sherman, S. J., and Ruvolo, C. M. (1990). Stereotype-based expectancies: effects on information processing and social behavior. J. Soc. Issues 46, 35–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb01922.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hawi, N. S., and Samaha, M. (2017). The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and list satisfaction in university students. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 35, 576–586. doi: 10.1177/0894439316660340

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hawley, G. (2011). Political threat and immigration: party identification, demographic context, and immigration policy preference. Soc. Sci. Q. 92, 404–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00775.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hello, E., Scheepers, P., and Gijsberts, M. (2002). Education and ethnic prejudice in Europe: explanations for cross-national variances in the educational effect on ethnic prejudice. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 46, 5–24. doi: 10.1080/00313830120115589

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hopkins, P. D., and Shook, N. J. (2017). Development of an intergroup anxiety toward Muslims scale. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 61, 7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.08.002

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ishii, K., Lyons, M. M., and Carr, S. A. (2019). Revisiting media richness theory for today and future. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 1, 124–131. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.138

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Islam, R. M., and Hewstone, M. (1993). Dimensions of contact as predictors of intergroup anxiety, perceived outgroup variability, and out-group attitude: an integrative model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 19, 700–710. doi: 10.1177/0146167293196005

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lee, D. K. L., and Borah, P. (2020). Self-presentation on Instagram and friendship development among young adults: a moderated mediation model of media richness, perceived functionality, and openness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 103, 57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.017

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, L., Zhang, Q., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Wang, T., Gao, T.-L., et al. (2020). Characterizing the propagation of situational information in social media during Covid-19 epidemic: a case study on Weibo. IEEE Transac. Comput. Soc. Syst. 7, 556–562. doi: 10.1109/TCSS.2020.2980007

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

López, M. H. (2009). Dissecting the 2008 Electorate: Most Diverse in U.S. History. Washington, D.C.: Pew Hispanic Center.

Google Scholar

Maddux, W. W., Galinsky, A. D., Cuddy, A. J. C., and Polifroni, M. (2008). When being a model minority is good and bad: realistic threat explains negativity toward Asian Americans. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 34, 74–89. doi: 10.1177/0146167207309195

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meeusen, C., Boonen, J., and Dassonneville, R. (2017). The Structure of prejudice and its relation to party preferences in Belgium: Flanders and Wallonia compared. Psychol. Belg. 57:52. doi: 10.5334/pb.335

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Müller, K., and Schwarz, C. (2019). From hashtag to hate crime: Twitter and anti-minority sentiment. SSRN Electr. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3149103

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1993). The Spiral of Silence: Public Opinion—Our Social Skin, 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Google Scholar

Nshom, E., and Croucher, S. M. (2017). Perceived threat and prejudice towards immigrants in Finland: a study among early, middle, and late Finnish adolescents. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 10, 309–323. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2017.1312489

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nshom, E., and Croucher, S. M. (2018). Other & first authoran exploratory study on the attitudes of elderly finns towards russian speaking minorities. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 11, 324–338.

Google Scholar

Pedhazur, E. J. (1997). Multiple Regression in Behavioral Research: Explanation and Prediction. Wodonga, VIC: Wadsworth.

Google Scholar

Rahmani, D. (2017). Minorities' communication apprehension and conflict: an investigation of Kurds in Iran and Malays in Singapore (Ph.D. thesis). University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, Finland.

Google Scholar

Relia, K., Li, Z., Cook, S. H., and Chunara, R. (2019). Race, ethnicity and national origin-based discrimination in social media and hate crimes across 100 US cities. Assoc. Adv. Artif. Intellig. 13, 417–427.

Google Scholar

Riek, B. M., Mania, E. W., and Gaertner, S. L. (2006). Intergroup threat and the integrated threat theory: a meta-analytic review. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 10, 336–353. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roulin, N. (2015). Don't throw the baby out with the bathwater: comparing data quality of crowdsourcing, online panels, and student samples. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 8, 190–196. doi: 10.1017/iop.2015.24

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rye, B. J., Merritt, O. A., and Straatsma, D. (2019). Individual difference predictors of transgender beliefs: expanding our conceptualization of conservatism. Pers. Individ. Dif. 149, 179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.033

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Schultz, F., Utz, S., and Göritz, A. (2011). Is the medium the message? Perceptions of and reactions to crisis communication via twitter, blogs and traditional media. Public Relat. Rev. 37, 20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.12.001

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Spencer, A. T., and Croucher, S. M. (2008). Spiral of silence and ETA: an analysis of the perceptions of french and spanish basque and non-basque. Int. Commun. Gaz. 70, 137–154.

Google Scholar

Spencer, A. T., Croucher, S. M., and McKee, C. (2012). Barack obama: examining the climate of opinion of spiral of silence. J. Commun. Speech Theater Assoc. N. D. 24, 27–34.

Google Scholar

Spencer-Rodgers, J., and McGovern, T. (2002). Attitudes toward the culturally different: the role of intercultural communication barriers, affective responses, consensual stereotypes, and perceived threat. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 26, 609–631. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00038-X

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stephan, C. W., Stephan, W. G., Demitrakis, K. M., Yamada, A. M., and Clason, D. L. (2000). Women's attitudes toward men: an integrated threat theory approach. Psychol. Women Q. 24, 63–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01022.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., Diaz-Loving, R., and Duran, A. (2000). Integrated threat theory and intercultural attitudes. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 31, 240–249. doi: 10.1177/0022022100031002006

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., and Renfro, C. L. (2002). "The role of threat in intergroup relations," in From Prejudice to Intergroup Emotions: Differentiated Reactions to Social Groups D, eds Mackie and E. R. Smith (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 191–207.

Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., and Stephan, C. W. (1985). Intergroup anxiety. J. Soc. Issues 41, 157–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., and Stephan, C. W. (1993). "Cognition and affect in stereotyping: parallel interactive networks," in Affect, Cognition, and Stereotyping: Interactive Processes in Group Perception, eds D. M. Mackie and D. L. Hamilton (Orlando, FL: Academic Press), 111–136.

Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., and Stephan, C. W. (1996). Predicting prejudice. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 20, 409–426. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(96)00026-0

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., and Stephan, C. W. (2000). "An integrated threat theory of prejudice," in Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, ed S. Oskamp (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 225–246.

Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., and Bachman, G. (1999). Prejudice toward immigrants: an integrated threat theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 29, 2221–2237. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00107.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., Martnez, C. M., Schwarzwald, J., and Tur-Kaspa, M. (1998). Prejudice toward immigrants to Spain and Israel. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 29, 559–576. doi: 10.1177/0022022198294004

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, P., and Morrison, R. (2009). "Intergroup threat theory," in Handbook of Prejudice, ed T. Nelson (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 43–59.

Google Scholar

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). "An integrative theory of intergroup conflict," in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–47.

Google Scholar

Troia, G. A., and Graham, S. (2017). Use and acceptability of writing adaptations for students with disabilities: Survey of Grade 3–8 teachers. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 32, 257–269. doi: 10.1111/ldrp.12135

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Valentova, M., and Alieva, A. (2013). Gender differences in the perception of immigration- related threats. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 39, 175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.010

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wen, J., Aston, J., Liu, X., and Ying, T. (2020). Effects of misleading media coverage on public health crisis: a case of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China. Anatolia 31:1–6. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2020.1730621

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yang, D., and Counts, S. (2018). Understanding self-narration of personally experienced racism on Reddit. Assoc. Adv. Artif. Intellig. 12, 704–707.

Google Scholar

macarthur-onslowprots1977.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00039/full

0 Response to "Why Were Chinese Workers Continually Harassed and Attacked Brainly"

Post a Comment